May the STEAM be with you

Jürgen Vollmer

On occasion of the Wave-Gothic Festival and the accompanying Steampunk Picnic in Leipzig

we explored on June the 7th how the industrial revolution and the accompanying scientific discoveries have been covered in science fiction and fantastic art.

We are very grateful that Prof. Elmar Schenkel jointed us on the tour,

and shared his vast knowledge about the Leipzig scholars in humanities, science and fiction.

Historical Context

We began the tour in the Physics building with a brief input about the contributions of the University of Leipzig to the development of modern technology, and about the eminent role of the city in the industrial revolution and the fight for workers rights.

The challenges brought forth by these developments were highlighted based on their coverage in

- Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon (1865), and its impact on the history of space travel. It inspired five different translations into English in merely twelve years after its appearance, and was a major inspiration for space missions that lead to the Apollo program.

- Fritz Lang: Metropolis (1927), and its visionary depiction of assembly line production, modern traffic, workers uprisings, and androids.

Fig 1. Introduction and start of the walk. Photos: Team WissensSpuren. The image to the left shows the cover of an early English translation of Jules Verne novel. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Moreover, in the late 1930s the Leipzig L-IV experiment was a first successful step to build nuclear power plants. Till the late 1970s they were expected to provide ample amounts of electricity and minimize the environmental impacts of the production of electricity.

Steam engines, Fechner, and Taro

In second half of the 19th century the Seeburg Quarter (region enclosed by the Nürnberger Straße, Brüderstraße, Talstraße, and Prager Straße) was an industrial quarter. In particular it was the location of the Philipp Swiderski’s factory for steam-powered printing presses1 and (portable) steam engines.

In the last third of the century the Southern part of that territory became the site of new buildings for the Samuel Heinicke School for hearing impaired people, the University Hospital, and a Science Campus that was erected also in response to the enormous fame of the polymath Gustav Theodor Fechner and his successor Wilhelm Eduard Weber who, together with Carl Friedrich Gauss, was the inventor of the first electromagnetic telegraph.

Besides as the founding director of the Institute of Physics in Leipzig, arguably the oldest physics institute of the world, Fechner is famous for his contributions as a founding father of psychology and in philosophy, where he was the first to speculate about the nature of space and time. In a direct line the latter speculations influenced H.G. Wells in his ideas leading to his famous novel The Time Machine.

Fig 2. Top left and bottom right: Photos of discussions in front of the Gerda Taro display at the Straße des 18. Oktober (© Team WissensSpuren). Top right: Woman training for a Republican militia in Barcelona, 1936. Gerda Taro, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Bottom left: Cover by Norman Saunders of the August 1950 edition of H.G. Wells’ novel “The Time Machine” in the magazine Famous Fantastic Mysteries, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It is quite remarkable how women are presented in the graphical adaptions of Wells’ novel (e.g. magazine cover in the lower left panel of Fig 2) — in particular when one contrasts them with Gerda Taro’s very modern-looking photos of women in the Spanish Civil War. Taro grew up in Leipzig, from where she was exiled in 1933. In Paris she became a pioneer of photography, arguably the first female photojournalist, and together with her partner Robert Capa she war the first war photographer. A striking aspect of her work are the images of women, who confidently train and engage in defending their believes, their families and their country (cf. top right photo in Fig 2).

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Leaving the Spanish Civil War2 we discuss the impact of train lines on our specification of time. Building train lines was heavily subsidized for military purposes, and the more efficient means of transportation brought forth a steep rise in industrial productivity in 19th century Saxony. However, setting up time tables for regular train connections was hampered by time standards that were traditionally set by a church tower. They were based on the solar time, and differed for community that do not share the same longitude. To resolve this issue train companies established their own times and pushed for a common standard. Finally, on the 1st of April 1893 the Central European Time was declared the common time for the German Reich. Standardization had become possible by that time based on the telegraph invented by Gauss and Weber.

Fig 3. Discussion at the Bayrischer Bahnhof (Photos: Team WissensSpuren). The engraving shown at the top right is a sketch by C. Bunnell that appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Public domain via Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The rising public awareness about subtleties in defining out time was taken up by Jules Verne in his novel Around the World in Eighty Days that appeared in 1872. Also in this case Jules Verne’s novel inspired the imagination of his contemporaries, and again it was a woman that set international standards. In 1890 Nellie Bly outcompeted Verne’s hero by preforming the trip around the world in merely 72 days, 6 hours, and 11 minutes. The mission was sponsored by Joseph Pulitzer’s tabloid newspaper and the New York World, and published as a book in the same year. The upper right panel of Fig 3 shows an engraving appearing in the news reporting her triumphant return to New York at the end of her trip.3

To fly or not to fly

For centuries Gargoyles were waterspouts protruding from Gothic buildings, like the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. They often took the form of dragon-like beasts, and they feature prominently (center panel of Fig 4) in illustrations of Victor Hugo’s Gothic novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

Fig 4. Looking at gargoyles and other grotesques (Photos: Team WissensSpuren). The engraving in the center shows Luc-Olivier Merson’s (1846–1920) engraving of Hugo’s Hunchback clasping a gargoyle of the cathedral Notre Dame de Paris, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the 20th century they came to life, making their appearance in L. Frank Baum’s Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908), Clark Ashton Smith’s Maker of Gargoyles (1932), the eighth season of the British science fiction television series featuring the time traveler Doctor Who (1971), and the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons (WG9, 1999).

Womanizers, Witches, and Wants of Wisdom

Arguably, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is one of the most influential German writers, and Faust is his most famous theater play. Goethe knew the topic from visits to Auerbachs Hof during his student years of study in Leipzig, where he led the life of an offshoot of a well-endowed family. Later in his life he became the chief adviser of the Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, and struggled to find time for writing and his ambitions in Science. His scientific work is mostly forgotten — but his writings persist; in particular passages like the description of the bacchanalia of the witches during the Walpurgis Night where one can hardly overlook the erotic subtext. The Bibliotheca Albertina holds one of Germany’s largest collections of historical hand-writings and correspondence that give a deeper insights into his quirks and ambitions.

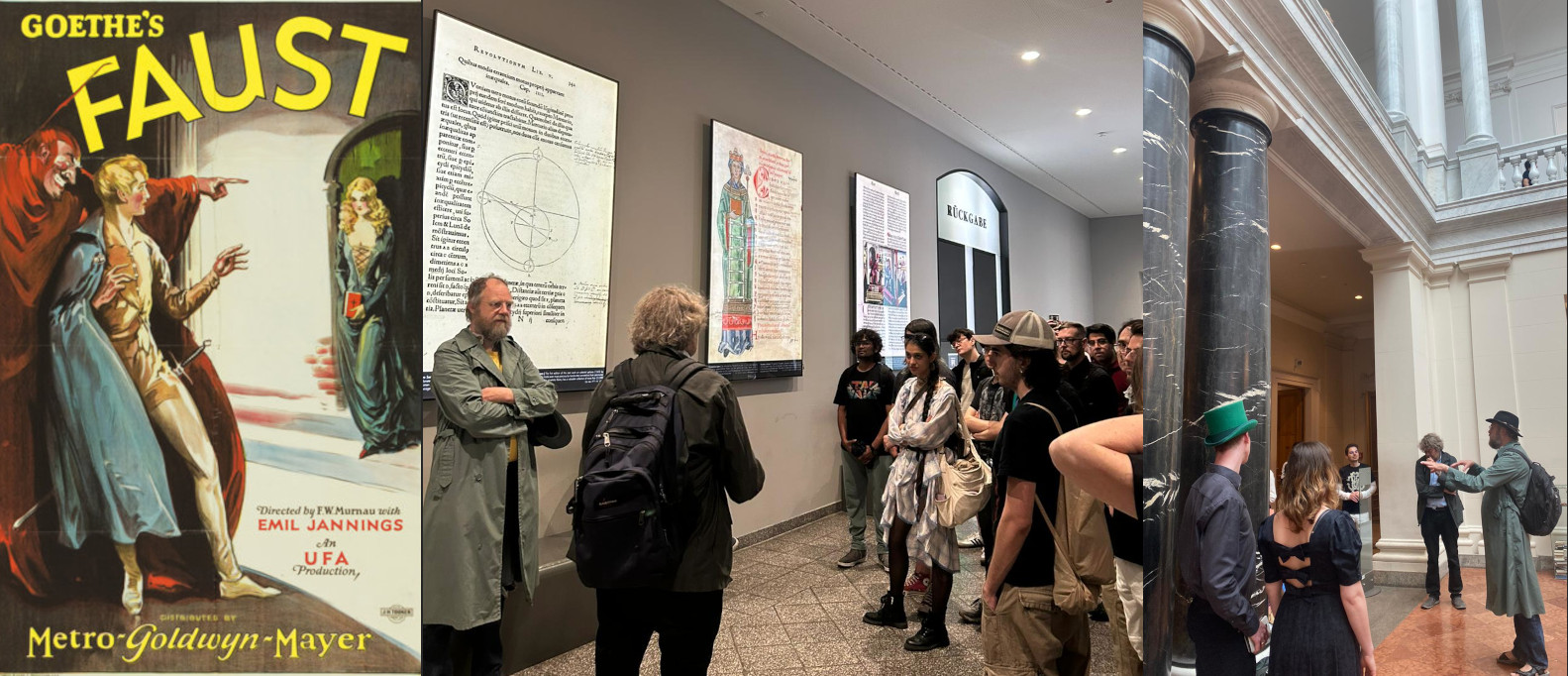

Fig 5. Witches in the Albertina (Photos: Team WissensSpuren). The poster on the left advertises Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s silent movie Faust (1926) for its U.S. release. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In contrast to Goethe the physicist and astronomer Johannes Kepler is well known for the scientific achievement of unraveling the laws of planetary motion. Kepler’s working copy of Nikolaus Kopernikus De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) is one of the treasures of the university library and displayed in as a facsimile in its permanent exhibition. However, it is not widely known that he performed this feat with the financial backing provided by the position of the imperial mathematician of Rudolf II of Habsburg, King of Hungary and Croatia, King of Bohemia and Archduke of Austria. His main responsibility in this task were precise astronomical observations, that were to be used for outstanding astrological advice. To promote his insights for a general audience Kepler composed an fictional story of a trip to the Moon, Somnium (1634) that gave him the opportunity to elaborate on how the perception of the stars will change upon moving the observer from the Earth to the Moon. Unfortunately, this early work of Science Fiction might have been the reason that his mother — with whom he is traveling in his fictional journey — was accused of witchcraft by malevolent opponents in times of religious wars.

Bombs, Spies, and Conscientious Objectors

We took our last stop in front of the Faculty of Theology, in order to recall the history of the Fuchs Family.

Emil Fuchs was a protestant theologian who was one of the first clergyman to join the social democratic party in Germany. He helped to set up local Adult Education Centers when he was priest in workers parishes in Rüsselsheim (1905) and Eisenach (1919), and he joined the Resistance during World War II. In 1949 he was appointed a professor in systematic theology and sociology of religion at the University of Leipzig. He explored the relationship of Marxism and Christianity, with a strict submission to pacifism that made him successfully fight for a possibility to opt out from military service and inscribe as a so-called construction soldier.

Fig 6. Discussions in front of the faculty of Theology (Photos: Team WissensSpuren). The comic in the bottom left is a page from Dr. Who and the Daleks, available under CC-BY-SA, via Tardis Wiki.

His son Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a brilliant student of physics in Leipzig, who emigrated the the UK in 1933 due to his political convictions. In the UK and the US he contributed to nuclear research to outcompete the German nuclear program that was prominently pushed by Werner Heisenberg and Robert Döpel in Leipzig (right at the starting point of our tour). Fuchs contributed to building the plutonium bomb Fat Man in Los Alamos, with John von Neumann he conceived the concept of the Hydrogen bomb, and after his return to the UK he became the head of the theory division of the British nuclear program. At the same time he was a communist spy who shared his knowledge to make sure that the Russian followed suit. After the emigration of his father to Leipzig he was uncovered, imprisoned, and after his release in 1959 he also emigrated to the GDR. Henceforth, he took a leading role in the Central Institute for Nuclear Physics in Dresden, and in the East German scientific councils for energetic basic research and for fundamentals of microelectronics. Einstein’s greatest anxiety has become true that the atomic bomb was brought into the world by a physicist from Leipzig.

Picnic in the Clara-Zetkin-Park

After the tour we joined the steampunk picnic in the Clara-Zetkin-Park for an informal get together. We had a splendit time in spite of a bit of rain.

Fig 7. Picnic in the Clara-Zetkin-Park. Photos: Team WissensSpuren

These presses were envisioned by Frederick Koenig during his apprenticeship with Breitkopf and Hartel in Leipzig. See Chapter VII in Samuel Smiles: Men of Invention and Industry. ↩︎

Indeed the title “For Whom the Bell Tolls” rings the bell of Ernest Hemingway’s novel describing the fate of a volunteer attached to a Republican guerrilla unit, the very same group of people portraits by Gerda Taro. ↩︎

Bly held the record for the fastest trip only briefly. Within a few month George Francis Train completed the journey in 67 days 12 hours and 1 minute. Indeed, in 1870 he had already completed such a trip in 80 days (albeit with interruptions), and arguably his trip inspired Jules Verne to his novel. By 1913 the trip was taken in less than 36 days, and presently the crew of the space shuttle completes a round after every 90 minutes. ↩︎